Friday, December 5, 2014

A Simple Bowl of Soup

A 101 East investigation traces the food footprint of a bowl of wonton soup. Along the way, they expose the toxic stew this soup has become. A very nasty business.

But this isn't about "Oh, look how bad it is in China." China is emblematic of the problems we face when the footprint of what we eat isn't transparent, isn't regulated and monitored, and isn't confined to one country.

Video sourced from Al Jazeera

Monday, November 3, 2014

A History of Fraud

76 samples of “goat cheese” from eight locations all around the UK were tested, and nine were found to have significant amounts of sheep milk in them. Three of those were more than 80% sheep milk, and three others were more than 50% sheep milk.After the horse-meat scandal, you would think that food fraud would be reduced. Apparently that's not the case.

This is not a new problem, nor is it restricted to the UK or even Europe. Modern Farmer also hosts an excellent long-form essay on the history of food fraud by Shoshanna Walter. Also included is this lovely list of food scandals. So go read the articles.

- 1 Swill Milk According to an 1860 New York Times story, the date that “swill milk,” milk polluted by cows fed with distillery runoff, got introduced to the New York population was unknown. But the effect was terrible. Babies fed the milk made by malnourished cows often died, and the backlash prompted landmark food safety hearings.

- 2 Leaded Wine As Bee Wilson chronicles in her book, Swindled, wine is a term that

contains multitudes: it can be infused with fruit or honey or lead. And

until the 1800s, although the evils of ingesting lead were known, there

was no real effort to stop pouring it into our wine glasses.

- 3 The Seal of Bread These days, one doesn’t hear much about poisonous bread, but securing standard ingredients and measurements for bread was a top priority in the Middle Ages, according to Bee Wilson. Bakers were held accountable by actually making a seal on their loaves, an early form of fraud detection, to prevent someone dumping coarse wheat into supposed refined products. The great Bread Scandal of 1757 involved alum being added and bread fraud persisted, by the the 19th century, people regularly stuffed birch bark and twigs into loaves.

- 4 Not-So-Green-Tea In an 1851 issue of British medical journal The Lancet, a shocking report was issued about a common beverage: green tea. In what became a scandal, it was found that green tea contained colorings and adulterants that included gunpowder. This scandal had been around for a while, as a counterfeit tea ring was prosecuted in 1818 for selling fake fancy varietals. With help from scientists, new methods were developed for testing the contents of tea.

- 5 The Great Lozenge Scandal The straw that broke the food regulatory back of Britain, according to Bee Wilson, was the Bradford sweets scandal of 1858. The candies were normally made with sugar and gum and some kind of cheap filler — usually plaster but, in this case, the candyman used arsenic. Over 200 people were poisoned — and 20 people died. In 1868, the government passed regulation to keep poisons like arsenic in the hands of chemists.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

The End of Inequality

|

| http://blogactionday.org |

The Americas were founded in genocide, built on slavery, and flowered by exporting the same form of colonialist activity around the world. Now, in late stage capitalism, the public good is trashed for corporate profit, financial speculation ensures hundreds of millions are left in near starvation, and corporate power has usurped the functioning of government of every stripe. The horror of it all is that we see this as normal, and not only haven't we strung up the offending parties, but instead, we do our best to emulate them. And, as Thomas Piketty has explicated in Capital, we have returned to an age when wealth is reserved for inheritors, not creators.

While what is now called the developed world has seen massive benefits from the Age of Carbon, all the undeveloped world has seen is warfare, exploitation, and destruction. Now, our addiction to hydrocarbons has reached the point where we are willing to destroy what groundwater we have left in order to pursue the last scraps of “wealth” left under our feet. Or, specifically here in Canada, we allow the First Nations people to die from poverty, to slowly die from myriad cancers, and to face starvation in order that a very few can become obscenely rich, and a few thousand more can become wealthy by world average standards. Meanwhile, our “democratic” governments must pay fealty to the exploiter class while our public infrastructure is destroyed by rising temperatures while impoverished local governments are left to struggle with the aftermath.

This all serves to maintain the illusion that the world around us in “normal.” Yet while we carefully kept the benefits to ourselves, we have dumped the costs on the environment (those un-payed-for externalities that business cannot survive without), and we've carefully lied to the bill collector so that those in the undeveloped world are pursued for the outstanding debt while we seemingly get off Scot-free. Island nations around the world are drowning in slow motion, drought and desertification spread across the equatorial and sub-equatorial world, and yet we allow foreign firms and governments to purchase unimaginably large swaths of the undeveloped world to produce food for export back to the developed world. We acquired the debt, but leave others to pay for it.

Ultimately, of course, the Great Mother doesn't give a rat's ass about our petty games. We don't figure this all out, she'll shake us off like so many dead skin cells, and give the planet back to the trees. We need to adopt the first tenet of the Hippocratic Oath (first, do no harm) as our guiding principle, or we can plan on seeing our children, our parents, ourselves, die slowly and horribly, crying out to an uncaring universe for succour.

Thursday, August 21, 2014

Living on an Acre

Living On An Acre 2nd edition: A Practical Guide to the Self-Reliant Life

U.S. Department of Agriculture Fully edited and updated by Christine Woodside

Lyons Press, © 2010

Guilford, Connecticut

ISBN: 978-1-59921-885-4

Originally published as Living on a Few Acres, and published in 1978, the original of this book was published to provide practical information and assistance to the back-to-the-land movement. This new edition is intended for the same audience although it focuses on smaller acreage. Living on an Acre walks a fine line between being encouraging and cautionary. It opens with a chapter titled “Pluses and Minuses” and the sub-section “Face the Realities” opens with a checklist:

- Do you want to be a part-time farmer on a few acres and keep a full-time job in town?

- Can you find a farm that suits your needs in a place where you are willing to live?

- How much will it cost? If more than your savings, can you obtain financing?

- Do you have the knowledge and skills needed to operate a small farm?

- What about financing the production process?

- How and where will you sell your produce?

When I worked off-farm, back in the day, I frequently found myself driving 5000 kilometres (3100 miles)/month—which drove me crazy. But the income paid for school supplies, utilities, and (of course) the ever increasing price of gasoline and car repairs. The insanity of working to afford the transportation costs of working is what lead us to the joyous moment of getting rid of our car and joining the Victoria Car Share Co-op.

I've considered the question of low farm incomes and have long wondered why farms don't take more of the process into their own hands. Selling, as we did, our production directly to the public through farmer's markets and the connections we made there, allowed us to receive a far more reasonable return. There were problems; getting up at 5:00 am to drive an hour and a half to Vegreville to have our chickens and turkeys processed (it has to be done at a licensed and inspected facility in order to be able to sell to the public rather than home use). The butcher we liked being forced out of small animal butchering by the lack of return, meaning we had to haul lambs to a abattoir we didn't really like in order to keep selling them. But, we could set a fair price for free-range animals and keep more of the money in our hands. And we ate like kings. But the loss of small, local slaughter operations isn't mentioned in Living on an Acre.

One of the great things about this book is the practical information it contains. How much land is needed for pasturing a horse? What are the housing requirements for goats? Should you build your own house? These are questions addressed here by the various writers. The must-read chapter is Growing and Raising: How to do it. The topics covered are great—from growing fruit trees, to nursery operations, to raising small and large stock, and even vacation farms. Traditional and non-traditional ways to provide yourself with an income get a good overview/introduction. The only lack is in marketing instructions. The sections on raising rabbits and chickens would be good reading for anyone contemplating raising these animals in the city.

Overall, this is a book that provides an introduction to many of the problems and concerns with moving to a rural life. The chapter The big picture offers short (often too short) essays from people who have made the transition. But Living on an Acre does offer the information you need in order to answer the questions the book ask. At the end of it, you'll have a better idea whether rural life is for you.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Jennifer and the City

Thursday, August 7, 2014

The Vampire Squid and the Garden

|

| Drought map via NOAA Yellow is lower level drought, dark red is higher |

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Monday, August 4, 2014

Everything Is Connected (Water Edition)

|

| Beluga photo via premier.gov.ru |

A while back I found out the whole story about why Beluga whales were washing up on the shores of the St. Lawrence around Montreal--whales whose carcases were so contaminated with toxins that they had to be handled as toxic waste. Turns out it had to do with farmers in the American Midwest applying fertilizer to their fields. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus was washing into the rivers in the (rather immense) Mississippi catchment basin, concentrating in the waterways, spilling out into the Gulf where it was creating a dead zone. Algae from the dead zone found their way up the Atlantic coast in blooms, generating the neurotoxin found in red tide. Various predators concentrated the toxin up the food chain as the bloom moved north, finally resulting in dead whales in the St. Lawrence. Everything is connected.

|

| Lake Erie photo via National Oceanic Service |

|

| microcystin-LR molecule via Toxmais, mostly because it's so frickin' cool! |

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Will The Soil Save Us?

|

| Image © Rodale Books |

It's an entertaining ride, very accessible to the lay reader. She briefly recaps the history of global warming (which should be known to every person on the planet by now, but, distressingly, is not), cruises through in introduction to soil microbiology, and then focuses the remainder of the book on permaculture practice through different characters and how they interact.

Friday, July 25, 2014

Problems/Solutions/Problems

|

| "Farming near Klingerstown, Pennsylvania". Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons |

But this is not my review of Soil, but the title is serving as a jumping-off point for some other things I've been reading and thinking about. Such as how we're facing this massive increase in population over the rest of this century.

It seems we're expected to increase world population from six to eight or nine billion before we top out. And somehow we need to feed all these people, an accomplishment made all the more difficult by peak oil, global warming, and the question of equitable distribution. The argument is made by industrial agriculture advocates that without high-tech, capital intensive farming, we'll never be able to feed everyone.

But here's the thing; modern agriculture is not a solution. Hell, pre-1900 agriculture is not a solution. Agriculture is the problem. Not the only one, true, but approximately a fifth of the problem. It's not that global warming will impact our ability to grow food in different areas, it's that growing food is contributing to global warming.

The FAO reports that:

[...]estimates of greenhouse gas data show that emissions from agriculture, forestry and fisheries have nearly doubled over the past fifty years and could increase an additional 30 percent by 2050, without greater efforts to reduce them.

[...]Agricultural emissions from crop and livestock production grew from 4.7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents* (CO2 eq) in 2001 to over 5.3 billion tonnes in 2011, a 14 percent increase. The increase occurred mainly in developing countries, due to an expansion of total agricultural outputs.

Meanwhile, net GHG emissions due to land use change and deforestation registered a nearly 10 percent decrease over the 2001-2010 period, averaging some 3 billion tonnes CO2 eq/yr over the decade. This was the result of reduced levels of deforestation and increases in the amount of atmospheric carbon being sequestered in many countries.

* Carbon dioxide equivalents, or CO2 eq, is a metric used to compare emissions from different greenhouse gases based on their global warming potential.

Monday, July 21, 2014

Flood Forecast--Bad And Getting Worse

|

| Image copyright Rocky Mountain Books |

[Is] one of the most unique non-fiction series in Canadian publishing. The books in this collection are meant to be literary, critical and cultural studies that are provocative, passionate and populist in nature. The goal is to encourage debate and help facilitate change whenever and wherever possible. Books in this uniquely packaged, hardcover series are perfect for general readers, academic markets and book lovers.

Friday, July 18, 2014

Our Daily Bread

|

| Photographer: Klaus Höpfner |

The Guardian's Damian Carrington reported yesterday (17 July, '14) that analysis of government data shows that some 60% of bread sold in the UK tests positive for pesticide residue, and that 25% of that tests positive for more than one pesticide.

The main offender? Glyphosate (also known as Round-Up). Rounding out the top three? Chlormequat, a plant growth regulator, and malathion, an organophosphate insecticide.

Interestingly, bread is much more likely to test positive for pesticide residue than other foods--which test positive "only" 40% of the time. Carrington reports:

The official tests are carried out by the government’s expert committee on pesticide residues in food (Prif) and the levels found were below “maximum residue level” (MRL) limits. The Prif experts concluded: “We do not expect these residues to have an effect on health.”

But environmental campaigners point out that these residues only indicate that pesticides were applied properly at source. But Nick Mole, at Pesticide Action Network UK (Pan UK) and an author of the new report on the government figures, points out that “[These residues] are nothing to do with people’s health whatsoever. There is the possibility of harm from the repeated ingestion of low doses of pesticides and no one has done research on the impact of the cocktails of pesticides we are all exposed to. We are all being experimented on without our consent.”

There doesn't seem to be any solid certainty about the effects of chemical residues in our food or bodies. But in Slow Death by Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things

|

| Stock image from Vintage Canada |

Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie point out that each of us in the developed world are carrying a "toxic load" of over 250 different chemical residues, and that we have no real idea of how our bodies react to the doses of each--let alone what happens in combination.

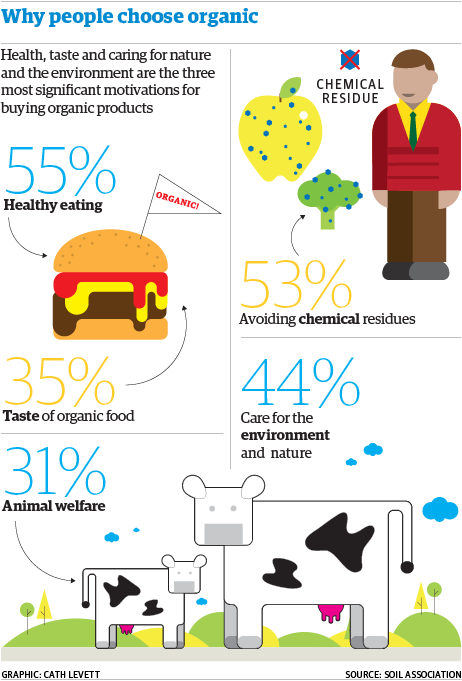

We can reduce our exposure to pesticides by buying and eating organic food, of course. Regardless of the controversy over whether organic food is more nutritious, we do know that residues are certainly lower (although possibly not non-existent) on organics. There are so many sources of contamination in our environment--from air, foam in furniture, to plastic microbeads in our water--it's nice to know we can actually do something about one source. And it can taste pretty good, too.

Thursday, July 17, 2014

Gone Feral. A Review.

|

| Image via novellacarpenter.net |

Novella Carpenter, the author of the excellent memoir Farm City: The education of an urban farmer, is back with a new book, Gone Feral: Tracking my dad through the wild. If you read her first book, about her move to Oakland and the founding of GhostTown Farm (and if you haven’t, you really should), you may think you know Ms. Carpenter and her dedication to creating rural environments inside an urban area. Channeling the spirit of the original English Diggers (and the later Digger movement in San Francisco, for that matter), she and her Significant Other Bill moved from Seattle to Oakland, fetching up in a rather less-than-savoury part of town. By turns heroic, crafty, and just plain lucky, Carpenter manages to take over an unused lot next to her rather tired apartment and convert it into an actual urban farm, raising everything from vegetables to chickens to some most memorable pigs. Step by step, Ms. Carpenter leads the reader through her unusual life, her unique neighbours, and her funky, and productive, farm.

|

| Novella Carpenter photo copyright Sarah Henry |

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

Books On My Desk part 1

These are just books that have accumulated on my desk and haven't made it to the bookshelves yet--from modern deconstructions of the food system to older books about food security. One in the latter category is:

The Home Vegetable Garden (Small holdings series-No. 2) produced by the Canadian Legion Educational Services, and published in 1945.

This book was apparently the second in a series of courses designed to train people in how to maintain a small holding. It starts out with stating that a quarter to a third of an acre should suffice to produce sufficient vegetables for fresh table use, canning, drying, and storing.

"Though a home garden, in most cases, will not provide the grower with a cash income and is not intended to, it will prevent the necessity of a very considerable cash outlay, it contributes to self-sufficiency, and of course 'a dollar saved is a dollar earned'."

It's a terrific little volume of about 175 pages, with chapters on general planning, bulb crops, perennial vegetable crops, potatoes, etc, with a short quiz at the end of each chapter. There's also information on storage of fresh and canned veg and disease control, and the whole is intended as a course at the end of which you've submitted an exam to be marked, and then you continue into the next course in the series.

Some of the info, like the recommendation to burn all plant trash at the end of the season (to help manage pests and disease) may have been superseded by the recommendation to compost everything (with the note that a good compost pile will heat up enough to sterilize weed seeds and kill pests), but things like how to build a temporary hotbed or coldframe are still quite valid. (A hotframe is a sprouting bed build over composting horse manure, which provides a warm environment to promote seedling growth. A coldframe is a small space that relies on passive solar to harden off early crop seedlings). Most interesting are the descriptions of various heritage seeds and what their strengths and weaknesses are. Some of these varieties are still available from places like Jim Ternier's Prairie Garden Seeds or West Coast Seeds in Canada. Overall, an excellent self-educator.

|

| image via Michael Pollan |

Michael Pollan's Food Rules: an eater's manifesto was the follow-up to In Defense of Food and is a collection of short epigrams to help the modern eater manage to supermarket jungle. "Avoid food products that contain more than five ingredients" is a perfect example; most processed, highly- or over-processed foods will contain more than five preservatives. This helps you remember to follow another epigram: "Shop the peripheries of the supermarket and stay out of the middle." Because the outside is where you find food--vegetables, meats, eggs, dairy. The aisles are where you find the over-processed near foods. The book is divided into sections that reference the summation of In Defense of Food: Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants. Which is still darned good advice.

|

| Image copyright Random House |

The Hundred Mile Diet: a year of local eating by Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon is very close to my heart. This book is as local as the diet they tried to stick to for a year. Packed with history, local colour, and the terribly engaging story of their decision to attempt to eat within an arbitrary perimeter for a year. That seemingly simple decision caused shock-waves around the world. It is partly because of this book that British supermarkets began tagging their goods with "food miles" stickers. The "grow local, buy local" movement got an enormous jump-start from this accessible and amusing read. In Canada, it lead the authors to the "Hundred Mile Challenge" television show and a remarkably down-home celebrity. Great writing+great concept+excellent timing=maximum impact.

The Story of Sushi: an unlikely saga of raw fish and rice by Trevor Corson (previously titled The Zen Of Fish, a fact I have to remember when I'm in the bookstore) is more than just a great bit of journalism. It's also where I see the non-fiction book evolving to--the after material contains extensive source notes, bibliography, index, and two brief bios of the author, a behind-the-scenes essay with a number of candid photos of the people we met in the books pages, an essay on the book tour on the books first release, and links to both the book and author's online presence (which is quite an extensive website and should serve as a template for any serious author in the digital age).

So that's pretty much a random grab.

Monday, July 14, 2014

The Rabbit Hole Revisited (Updated)

As I posted in The Rabbit Hole the other day, there are a number of studies about organic food coming out these days, some of which are focused on whether or not organically-raised foods are nutritionally better for you. Industrial agriculture is clearly getting worried about public perception, because they are forming astroturf groups (groups that look like they're grassroots, but are actually funded and directed by industry) as part of their push-back against alternatives to the industrial food system. It is an expected strategy now that Big Tobacco owns such a big piece of the manufactured food-like substance industry.

Well, sure as the "super moon" has arrived, so has another study made it into the media. The Guardian has reported on one in an article titled "Clear differences between organic and non-organic food, study finds." The article begins:

Organic food has more of the antioxidant compounds linked to better health than regular food, and lower levels of toxic metals and pesticides, according to the most comprehensive scientific analysis to date.The study cited is Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. There's a lot of what Stepghen Stills called "hooray for our side" going on. The British Soil Association cheers the report for showing that "this research [...] shatters the myth that how we farm does not affect the quality of the food we eat."

The international team behind the work suggests that switching to organic fruit and vegetables could give the same benefits as adding one or two portions of the recommended "five a day".

Of course, there is an opposing viewpoint: Tom Sanders, a professor of nutrition at King's College London said "he was not persuaded by the new work. "You are not going to be better nourished if you eat organic food," he said. "What is most important is what you eat, not whether it's organic or conventional. It's whether you eat fruit and vegetables at all. People are buying into a lifestyle system. They get an assurance it is not being grown with chemicals and is not grown by big business."

So the question of whether organically grown food is nutritionally better for you is still not a solved puzzle. Mostly because nutrition is not a solved puzzle. Despite all the research being produced and released, and commented on by and in the media, we still have no really good idea about what any of the research means. Because double-blind human trials would be unethical, we will probably never definitively know what any of this research does and doesn't mean.

The Guardian, to its credit, does try to address this in a piece by Karl Mathiesen titled Will eating organic food make you healthier? After some back-and-forthing with various studies, claims and counter-claims, there is actually a follow-up interview with one of the study's lead authors, Carlo Leifert where he gets to respond to some of the claims and criticisms around the study. Some of the criticisms and his responses?

Cadmium variation usually results from soil variation:Mathiesen's article is noteworthy for taking a lot of the politics out, and adding a fair bit of the science back in to the whole "is organic better" argument. There's also a link to a great reproduction of an old article called The Organic Movement by Colin Mares (?), which shows that some of these arguments go back decades.

"We are pretty certain that soil type is averaged out over the many studies [we analysed]."Higher cadmium levels in conventional crops are still within safe legal limits:

"But cadmium accumulates in the body - you really want to avoid eating it if possible."Pesticides levels is conventional foods are also beneath maximum recommended levels:

"But there are some conventional crops that do exceed levels (eg 6% of spinach - see paper for more examples). If you want to avoid that it would be helpful to eat food with a lower chance of pesticides. until they start testing combinations of pesticide I am not confident in the regulatory testing regime."

UPDATE:

Another excellent piece by Nathanael Johnson at Grist on the controversy ( can it really be a controversy when both sides are arguing from positions of scientific uncertainty?).

But what we do know is clear: organic food exposes us to fewer pesticides and herbicides and is better for the soil. And that Industrial Organic is not the same as Sustainable Organic. So buy local organic when you can, and plant a garden (or a plot, or a balcony, or a pot in the window).

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Awareness vs Understanding

(There's supposed to be an embedded video above, and the code's all there,so here's hoping...)

Knowing the numbers are important, but understanding what's going on behind the numbers is more important. This is the difference between awareness and understanding. If I'm aware that food is being wasted and contributes to global warming, that's great. But it doesn't give me the information I need to change anything.

Understanding the causes of problems can offer you the chance to make a difference--either in your own life and sphere of influence, or on a larger scale. Information must have a component of action attached to it, or it is nothing more than noise.

I've just started reading Life Rules

by Ellen LaConte, in which she uses AIDS as a metaphor for the complex multilevel assault on life on Earth. To draw from that idea, ACT-UP insists that "Silence=Death." In the case of the current "Critical Mass of cascading environmental, economic, social and political crises", Inaction=Death.

But the best book I've read recently (Recently, because Raj Patel and Marion Nestle were a couple of years back) has to be John Michael Greer's book Decline and Fall: The end of empire and the future of democracy in 21st century America.

Greer points out some hard truths about our future, such as it takes power to create an alternately-powered future. Power we don't have and probably never will have. And that means that the current civilization we have is pretty much over. The best we can hope for, according to Greer, is something approximating a 1910 standard of living. You know, if we're lucky, smart, and get on the ball. And one of the ways he sees this happening is through small organization democracy.

Now, I don't know if his solution is the only right one, but I do know that it will cost nothing to try. So I recommend reading his book and getting on with changing the world every way you can.

Tuesday, July 8, 2014

Dang. Now I'm Hungry.

I don't know about you, but leftover milk, or milk that's past useability, really never appears at our house. But it seems that it does in a lot of houses--in the UK there's 290,000 tonnes of milk wasted each year. All part of that wasted 30-50 percent of food in developed countries.

But over at The Guardian, Rachel Kelly has a few (well, 14) ways to deal with leftover milk. I'm more likely to have made too much rice and be looking for a way to use it that doesn't involve making another stir fry. My favourite use is by making rice pudding.

I brought a rice pudding to one of the Friday lunches we attend at the Centre for Community and Cooperative Based Economies (CCCBE) at the University of Victoria. it was my standard, adjust-for-size recipe:

- a couple or more eggs

- beaten with vanilla, a pinch of salt, some sugar and cinnamon or nutmeg

- some cooked, leftover rice

- a small handful of raisins

- milk sufficient to cover the rice

- remixed and baked at 175C or 350F until a lovely light brown shows up on top and the pudding is set.

- Best served hot with cream over top.

I've eaten this as breakfast, lunch, dinner, and as a snack food, simply because it tastes good and qualifies as comfort food for me (and, nutritionally, isn't too bad either).

But when I presented this for lunch, one of the attendees was confused; a visiting scholar from Iran, this was nothing like the rice pudding he was used to. So the next week, he had his wife create one of her rice puddings. Short grain white rice cooked in milk to create a porridge. Sweetened and spiced with cardamon and cinnamon (among others). Served cold.

And wow! What a difference! Light and flavourful, I was transported to a shady courtyard on a hot summer day. My rice pudding is hearty and filling. This is a cool light treat. Similar ingredients, radically different end result.

This is why I love the whole free trade in recipes thing. There's so much to learn that no one can learn it all. And there are so many great flavours to discover.

Monday, July 7, 2014

The Rabbit Hole

|

| Burial chamber of Sennedjem, Scene: Plowing farmer. Public Domain |

Back on 02 July, Alexis Keinlen retweeted a blogpost suggesting that the differences between organic and "conventional" farming (I always understood that organic was the historically conventional method of farming, but hey...) were not that different. As an example, organic farming has it's own suite of pesticides that are sprayed on fields.

I was quite disappointed by the lack of information contained in the post at Real Clear Science. It cited two systematic reviews, one in the Annals of Internal Medicine (tucked behind a paywall I have no access through), and the other in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The abstract of the first study states in it's conclusion: "The published literature lacks strong evidence that organic foods are significantly more nutritious than conventional foods." (italics mine). The second study, in AJCN, says:

To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review to assess the strength of the totality of available evidence of nutrition-related health effects of consumption of organic foodstuffs. Despite an extensive search strategy, the review only identified 12 relevant articles that met our inclusion criteria and were published, with an English abstract, in peer-reviewed journals over the past ≥50 y. The identified articles were very heterogeneous in terms of their study designs and quality, study population or cell line, exposures tested, and health outcomes measured. This inherent variability prevented any quantitative meta-analysis of the reported results, and from our narrative review, we concluded that evidence of nutrition-related health effects from the consumption of organic food is currently lacking.Ross Pomeroy, who wrote the blogpost at RCS, has this as his takeaway: "The majority of Americans believe that organic foods are healthier than food grown using conventional methods. The majority of Americans are wrong."

But that's not actually what the studies say. Both quotes above use similar language, saying that "evidence is lacking." There is not a statement that organic food is more or less nutritionally good for you. Rather, there is no evidence either way. A study in Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition sums it up best in it's abstract:

Studies comparing foods derived from organic and conventional growing systems were assessed for three key areas: nutritional value, sensory quality, and food safety. It is evident from this assessment that there are few well-controlled studies that are capable of making a valid comparison. (emphasis mine)Pomeroy dismisses the claims that organic food is any better for us nutritionally very quickly, and moves on to a jeremiad against organic agriculture for using various pesticides approved under the USDA organic standards. He claims that these sprays are less effective than those used by industrial agriculture and are frequently more damaging to the environment. There is some evidence he may be correct. But he relies on a piece in Academics Review, a site which is itself rather suspect as being an astroturf-type site (being industry-funded propaganda disguised as posts by disinterested parties. A practice that goes back to the Big Tobacco wars).

The website for Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR) points out:

The Koch brothers are the conservative billionaire co-owners of a conglomerate of chemical and oil companies, including Koch Ag & Energy Solutions. They and other biotechnology/chemical companies have a lot to lose from the explosive growth of pesticide-free organic foods.

Academics Review claims to be an independent “association of academic professors, researchers, teachers and credentialed authors” from around the world “committed to the unsurpassed value of the peer review in establishing sound science.”

However, recent articles on its website and Facebook page paint a picture of industry-biased, agenda-driven organization focused on discrediting public interest organizations, organic companies, media outlets and scientists who question the safety of GMOs and pesticides, or who tout the benefits of an organic diet.

The co-founder of Academics Review is Bruce Chassy, a recently retired professor of food microbiology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Chassy was among 11 scientists named by the Center for Science in the Public Interest in a complaint (8/21/03) to the journal Nature for failing to disclose “close ties to companies that directly profit from the promotion of agriculture biotechnology.”

As the letter notes, Chassy “has received research grants from major food companies, and has conducted seminars for Monsanto, Genencor, Amgen, Connaught Labs and Transgene”—companies with a large financial stake in pesticides and GMO technologies designed to boost pesticide sales.

Chassey is also on the advisory board of the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), a group that bills itself as an independent research and advocacy organization devoted to debunking “junk science.” Carl Winter, one of Slate’s key sources, is also on the ACSH board.

However, as Mother Jones (10/28/13) revealed in a expose based on leaked documents, ACSH’s funders include agribusiness giants Syngenta and Bayer CropScience, as well as oil, food and cosmetics corporations that have a vested interest in getting consumers to stop worrying about the health effects of toxic chemical exposures.