|

| via Wikipedia |

Would you like to

know what your world is going to look like by, say, 2030? A little

peek at the wonderful things we’ll be using? Lives we’ll be

living? Did vat-grown meat ever become a thing? Are more of us

vegetarian? How did that whole Trump presidency work out?

Getting a look is

easier than you think. All we have to do is look at Puerto Rico

today. Today Puerto Rico is a land of sunshine, environmental

devastation, and the threat of starvation.

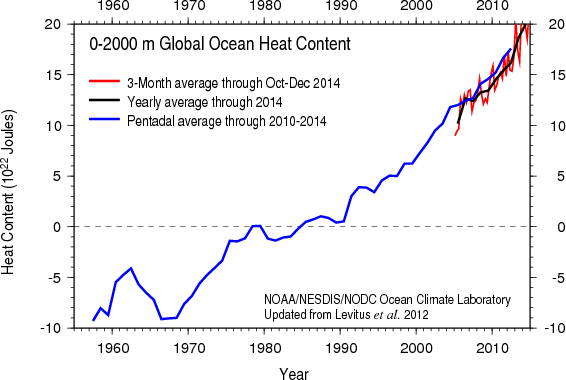

This year has seen

three major global warming-intensified storms hit in the Caribbean

and southern US in a row. One, Irma, was rated a Category 5 only

because there is nothing higher than C5. This is pretty much exactly

in line with NASA, NOAA, and international modelling of the effects

of a warming planet. The ocean has been soaking up amazing amounts of

both carbon and heat over the last couple of decades. Now, when a

depression forms over the ocean, there is much more energy available

for it to soak up. And the more energy it gets from a warmer ocean,

the bigger the eventual storm.

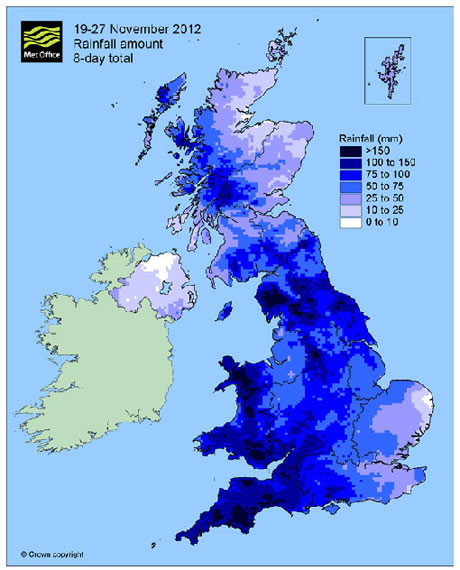

On the West Coast of

North America, this will play out in two ways; the warming ocean will

also create larger storms, and the warmer air will pick up more

water. As little as 1/2 of one percent more moisture in the air can

lead to an increase of fifty millimetres or more (2”+) of rain.

With the logging of the last century, this will mean more mudslides,

silting of rivers, damage to spawning grounds, and impacts on

municipal water supplies.

On the US’ south

and East coasts, storms, particularly hurricanes, will be larger,

more damaging, and bring more flooding with larger storm surges. Maria, the hurricane that

has wiped our about 80% of Puerto Rico’s crops and up to 80% of

some neighbourhoods, is the third storm to hit US territory. This too

is in line with the models. And it is this sequentiality that is the

problem.

In Houston TX, some

places recieved over a metre of rain in 24 hours. As the centre of

the US petrochemical industry, Houston has claimed the lion’s share

of US aid. Florida recieved much of the rest. Puerto Rico, not being

a state but rather a protectorate, is coming a poor third. It doesn’t

hurt that both Texas and Florida voted heavily for the current

president.

This is one year.

What will it be like when we’ve had a decade or more of these

disasters. Drought and wildfire in the Midwest, or wildfire or floods

on California. In Canada, the prairies are overdue for a drought, a

wildfire almost took out Ft. McMurray last summer, and the interior

of BC has been devastated by one this summer. Insurance against

natural disasters is becoming harder to get, and insurance companies

are losing their collective minds.

So here’s the

thing about Puerto Rico: 80% of their food crops have been destroyed.

The protectorate is poor. And, as Amartya Sen has pointed out, in

order to survive famine, you have to be able to either buy food in

the market, or move to where you can buy or grow food. And the US has

been exploiting the fact that if you just provide food aid, you

destroy the local markets, making the population dependent on

provided food. It’s actually better to slowly substitute money for

food aid, in order to build the market back up.

So what are the odds

that the current US government will provide a guaranteed annual

income to the residents of Puerto Rico? Because it will take years

for PR to recover (if ever—there are more storms coming). Or Puerto

Rico becomes a state of refugees, moving en masse to the

continental United States. And how do you think that’s going to go

over in the present political environment in the US?

That’s your future

too. There will be a storm. Or another natural disaster. And the

country will be overextended, so disaster relief will be limited or

non-existant. So you either try and rebuild where you are, or become

an internal refugee.

Murphy’s Law

dictates that when the disaster hits, it will destroy the most

important stuff; transportation corridors, the electrical grid, food.

Just like Puerto Rico. And that it will happen at the worst time. The

1% think they can get out of this—it’s why Elon Musk wants to go

to Mars. It’s why they’re buying bunkers in New Zealand. And it

won’t help.

We cannot keep going

the way we are. That route means we’re reduced to a hundred

thousand humans, or so. Worst case, we turn the planet into Venus for

a couple of million years. As Michael Crichton said in Jurassic Park:

“I don’t fear for the future of life on Earth. [...] I fear for

the future of human life on Earth.” We have to downshift in a

radical way. Converting to sustainable power doesn’t mean we get to

keep this life of insane consumerism. Sustainable power means that we

live a medieval life in some comfort. If we start yesterday, we might

be able to keep the losses to a few billion humans.

.svg/800px-Instrumental_Temperature_Record_(NASA).svg.png)