|

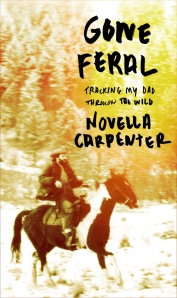

| Image via novellacarpenter.net |

Novella Carpenter, the author of the excellent memoir Farm City: The education of an urban farmer, is back with a new book, Gone Feral: Tracking my dad through the wild. If you read her first book, about her move to Oakland and the founding of GhostTown Farm (and if you haven’t, you really should), you may think you know Ms. Carpenter and her dedication to creating rural environments inside an urban area. Channeling the spirit of the original English Diggers (and the later Digger movement in San Francisco, for that matter), she and her Significant Other Bill moved from Seattle to Oakland, fetching up in a rather less-than-savoury part of town. By turns heroic, crafty, and just plain lucky, Carpenter manages to take over an unused lot next to her rather tired apartment and convert it into an actual urban farm, raising everything from vegetables to chickens to some most memorable pigs. Step by step, Ms. Carpenter leads the reader through her unusual life, her unique neighbours, and her funky, and productive, farm.

Gone Feral on the other hand, is a different sort of journey, but still told in a unique and compelling voice. Spare prose, clear progression, and a dedication to telling the story of the day her father went missing, and her (re) discovery of him, make for a compelling read. I had expected to enjoy the book based on my experience with Farm City, but I hadn’t expected to become so wrapped up in the read that I ate this book in one gulp (with several cups of tea).

Novella’s parents were part of the hippie/alternative/back-to-the-land movement of the late 60s and early 70s. They found and purchased some lovely land outside Orofino, Idaho. They moved into a battered mobile home, slowly built their own house, gardened, raised animals, found local work, and fell apart. Regretfully, not a unique story from that (or this) time. Her mother moved to the Pacific Northwest with Novella and her sister, and her father stayed behind. Then, on October 17th, 2009, Novella received a call that her father was missing. Although he resurfaced some weeks later, none the worse for the wear, the experience sent Ms. Carpenter off on a quest to find her father.

This is primarily a book about a daughter trying to reconnect with her father, struggling to understand his life and choices, and, most importantly, trying to figure out what happened. Throughout the book there are reasons, revelations, and reconnections, and the resolution, this being real life and not a novel, may not be as satisfying as you might hope (although I found a deep resonance with it). But almost by accident, Carpenter addresses a topic that I have been considering for some time (and written about here on the blog): why were there so many failures in the back-to-the-land movement?

|

| Novella Carpenter photo copyright Sarah Henry |

We see Carpenter’s parents meet and move onto a farm in Idaho. We see how difficult it was for them as a couple and family to achieve their dreams (and how much of the dream became a nightmare). And as Novella negotiates her father’s history, many of the reasons for the failure become clear. But across the holler from her parents are some other back-to-the-landers. And they, ultimately, are not a failure.

Novella describes the differences between the Carpenters and their neighbours: the Carpenters are alone, following the homesteader narrative of America. The neighbours? To begin with, there are two couples. After some time, they build a second house on the property. They invite their neighbours to an annual solstice party.

The homesteader narrative of America is a myth. Particularly in the east, the settlers were moving onto farms that were established, had been cultivated for decades if not longer, often had full storehouses of food and seed, and in many ways, were better than their equivalents in Europe at the time. It was just that their occupants had recently died from contact with the European settlers. There was very little of the “two people and a horse” homesteading

happening at all. But the myth of an empty land and heroic settlers was much more satisfying than the reality of “we killed them all and took their stuff.”

And it was this myth that led so many landers astray. The belief that you had to do it all alone, that you had to be totally self-sufficient, that belief doomed them.

The Farm, the collective founded around the same time as the Carpenter’s began their attempt, succeeded, and still survives. But that was because the people who founded The Farm took their community with them, and built links with the local community. The Carpenter’s neighbours took a smaller community with them, but also built links with the local community. They made friends, asked advice, lent a hand. In short, mutual aid trumps self-sufficiency. And it’s no different today.

In Gone Feral, Novella carpenter explores a family history that “does not repeat, but rhymes.” So to does the current rural repopulation rhyme but not repeat. In the former, the story is compelling and extremely readable. In the latter, the story is not yet done.

thank you for sharing!

ReplyDelete