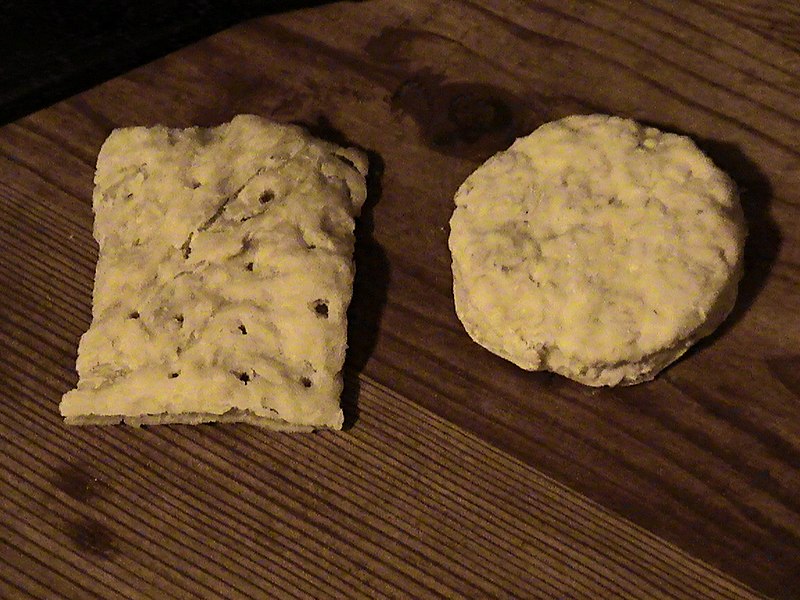

What we're not really thinking about is why the sailors faced scurvy in the first place. Navy life was brutal, badly paid, and if you weren't an officer, you were the lowest of the low—roughly equivalent to footpads and cut-purses. And the food was horrible. In the damp confines of the ship, everything developed moulds and spoiled, there was no refrigeration, and food storage techniques were less than effective. Hardtack, or ship's bread, was nothing much more than flour, water, and maybe salt, fashioned into a biscuit and baked four times to drive all the water out of it. Properly prepared, it would last effectively forever on board ship, but provided a badly nutrient-deficient food for sailors.

|

| Reproduction hardtack (from wikipedia) |

Turns out, they're not. Research over the last three or four years is showing that not only may they not be doing us any good, but they are actually being linked to earlier death in certain populations (primarily women). There are questions being raised about dose absorption from pills, timed-release seems to mean poorer uptake rates, and on and on.

In response, we hear people saying “All you have to do is eat properly and you won't need supplements.” Hey, I've said it myself. Concentrate on cooking from scratch, use lots of whole vegetables rather than processed ones, and everything should be fine. Except... it's probably not fine. Thomas F. Pawlick, in his book The End of Food (a good Canadian boy, btw. And what is it about Canadians that they write so many excellent books about the food system?) talks about a number of tests—Canadian, American, and British—that show similar results: over the last half century or so, the nutritional content of food has changed. And seldom for the better.

|

| Thomas F. Pawlick |

In 2002, André Picard reported on a joint investigation by CTV and the Globe and Mail that looked at nutritional content of six fruits and vegetables. They published this table of the changes in the nutritional make-up between 1951 and 1999:

Food

|

Calcium

|

Iron

|

Vitamin A

|

Vitamin C

|

Thiamine

|

Riboflavin

|

Niacin

|

Apple

|

20.0

|

-55.3

|

-41.1

|

16.0

|

-75.0

|

-66.7

|

-30.0

|

Banana

|

-23.8

|

-41.7

|

-81.2

|

-13.0

|

0

|

-100.0

|

-1.4

|

Broccoli

|

-62.8

|

-33.9

|

-55.9

|

-10.1

|

-40.0

|

-42.9

|

-2.7

|

Onion

|

-37.5

|

-52.9

|

-100.0

|

-54.8

|

56.9

|

-41.2

|

135.3

|

Potato

|

-27.5

|

-58.6

|

-100.0

|

-57.4

|

-14.6

|

-50.0

|

44.9

|

Tomato

|

-55.7

|

-18.8

|

-43.4

|

-1.6

|

0

|

21.8

|

46.3

|

Notice how some of the listed foods have lost all their nutritional content in one category or another: Bananas have lost all their riboflavin, Onions and potatoes have lost all their vitamin A. And across these seven categories, the majority have lost significant amounts of nutritional value.

In the UK, the story is similar. British researcher Anne-Marie Mayer published a study called Historical Changes in the Mineral Content of Fruits and Vegetables [pdf] (British Food Journal, 99(6), 1997, 207-211) in which she wrote:

In the UK, the story is similar. British researcher Anne-Marie Mayer published a study called Historical Changes in the Mineral Content of Fruits and Vegetables [pdf] (British Food Journal, 99(6), 1997, 207-211) in which she wrote:

There were significant reductions in the levels of calcium, magnesium, copper and sodium in vegetables, and magnesium, iron, copper, and potassium in fruits. The greatest change was the reduction in copper levels in vegetables to less than one-fifth of the old level. The only mineral that showed no significant differences over the 50-year period was phosphorus. [p. 209]

Pawlick has also looked into the US experience, particularly that of tomatoes. “Tomatoes were once among the best sources of these vitamins [A and C]. But 100 grams of today's fresh tomato contain 30.7 percent less Vitamin A and 16.9 percent less Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) than its 1963 counterpart. [emphasis in original] It also has fully 61.5 percent less calcium [...], 11.1 percent less phosphorus, 9 percent less potassium, 7.97 percent less niacin, 10 percent less iron and 1 percent less thiamine.” [p. 6 The End of Food]

That's since 1963—the numbers look worse if you go back to the nutrient tables produced by the USDA in 1950. Then it becomes apparent that while the tomato may be down 10 percent in its iron content since 1963, it is down 25 percent since 1950. But there are increases as well: fats (lipids) are up by 65 percent and sodium is up by 200 percent.

This is also true in processed tomatoes; canned tomato juice is down 35.4 percent on iron content and 30.5 percent of its Vitamin A—again since 1963. Vitamin A is down 47 percent in tomato juice since 1950. And these are only the primary vitamin and mineral components that have been measured. We really have no idea as to any change in the micro-nutrient component of what we're forced to consider as food.

So conventional agriculture has left us with an ongoing legacy of lots of cheap food, but of declining nutritional value. [Oh, and don't you love that bit of Orwellian Newspeak? Industrial agricultural methods—only about 60 years old—are referred to as “conventional,” while the techniques that date back to the beginning of agriculture have their own, separate classification of “organic.”] To replace the missing nutrients, we're expected to pick up oral multivitamins—which may or may not be bio-utilizable and which seem to shorten some lifespans.

What's to be done? It's pretty straightforward; begin cutting industrially-produced foods out of your diet. Replace it with homegrown food (because most of the changes in the various cultivars has been to increase storage life and transportability) grown from heritage seeds. Save your own seed and plant in good quality soil replenished with compost from your food waste. Preserve your own food wherever possible (really, its not that difficult). Even if you can't be entirely self-sufficient (and that is difficult to do), you can be a great deal more self-reliant and reduce your intake of poor quality food by replacing it with high-quality real food.

That's since 1963—the numbers look worse if you go back to the nutrient tables produced by the USDA in 1950. Then it becomes apparent that while the tomato may be down 10 percent in its iron content since 1963, it is down 25 percent since 1950. But there are increases as well: fats (lipids) are up by 65 percent and sodium is up by 200 percent.

This is also true in processed tomatoes; canned tomato juice is down 35.4 percent on iron content and 30.5 percent of its Vitamin A—again since 1963. Vitamin A is down 47 percent in tomato juice since 1950. And these are only the primary vitamin and mineral components that have been measured. We really have no idea as to any change in the micro-nutrient component of what we're forced to consider as food.

So conventional agriculture has left us with an ongoing legacy of lots of cheap food, but of declining nutritional value. [Oh, and don't you love that bit of Orwellian Newspeak? Industrial agricultural methods—only about 60 years old—are referred to as “conventional,” while the techniques that date back to the beginning of agriculture have their own, separate classification of “organic.”] To replace the missing nutrients, we're expected to pick up oral multivitamins—which may or may not be bio-utilizable and which seem to shorten some lifespans.

What's to be done? It's pretty straightforward; begin cutting industrially-produced foods out of your diet. Replace it with homegrown food (because most of the changes in the various cultivars has been to increase storage life and transportability) grown from heritage seeds. Save your own seed and plant in good quality soil replenished with compost from your food waste. Preserve your own food wherever possible (really, its not that difficult). Even if you can't be entirely self-sufficient (and that is difficult to do), you can be a great deal more self-reliant and reduce your intake of poor quality food by replacing it with high-quality real food.

No comments:

Post a Comment